Introduction

In our fast-paced world, sleep often gets sacrificed in favor of work, social activities, or entertainment. Many people operate under the assumption that they can function adequately on minimal sleep, but this approach ignores a fundamental biological reality: your body and brain have non-negotiable sleep requirements known as core sleep.

Core sleep represents the essential, minimum amount of sleep your body needs to maintain basic physiological and cognitive functions. It's the sleep you cannot skip without experiencing significant negative consequences. Understanding your core sleep needs is crucial for maintaining health, performance, and well-being.

This article explores what core sleep is, how it differs from optimal sleep, how to identify your personal core sleep requirements, and strategies for ensuring you meet these essential needs even in challenging circumstances.

Defining Core Sleep: The Essential Minimum

Core sleep is the minimum amount of sleep required to maintain basic biological functions and prevent severe sleep deprivation. It's not the amount of sleep that makes you feel great or perform at your best—it's the amount you need to avoid serious health consequences and maintain basic cognitive function.

The Biological Basis of Core Sleep

Core sleep is determined by several biological factors:

- Circadian rhythm: Your internal clock regulates when you need to sleep and wake

- Sleep pressure: The build-up of adenosine and other sleep-promoting substances

- Homeostatic regulation: Your body's need to balance sleep and wakefulness

- Genetic factors: Individual variations in sleep need and sleep architecture

Research suggests that most adults require approximately 5-6 hours of core sleep, though this varies significantly between individuals. This minimum includes essential sleep stages that cannot be skipped without consequences.

What Core Sleep Includes

Core sleep must include adequate amounts of:

- Deep sleep (N3): Essential for physical restoration, immune function, and memory consolidation

- REM sleep: Critical for emotional processing, creative thinking, and procedural memory

- Light sleep (N2): Important for memory consolidation and information processing

Missing any of these stages can lead to specific deficits in function, even if total sleep time seems adequate.

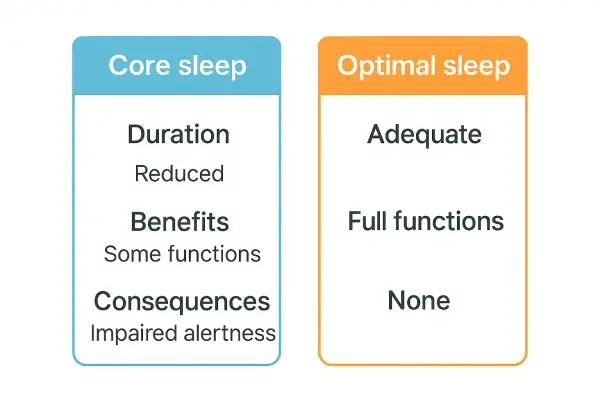

Core Sleep vs. Optimal Sleep: Understanding the Difference

It's important to distinguish between core sleep and optimal sleep, as they serve different purposes and have different implications for health and performance.

Core Sleep: The Survival Minimum

Core sleep is about survival and basic function. When you get only core sleep, you can:

- Maintain basic cognitive function

- Avoid severe sleep deprivation symptoms

- Keep your immune system functioning

- Prevent serious health consequences

However, core sleep alone doesn't provide:

- Peak cognitive performance

- Optimal emotional regulation

- Enhanced creativity and problem-solving

- Maximum physical recovery

- Long-term health optimization

Optimal Sleep: The Thriving Standard

Optimal sleep (typically 7-9 hours for adults) provides all the benefits of core sleep plus:

- Enhanced memory and learning

- Better emotional regulation and mood

- Improved creativity and insight

- Optimal immune function

- Better physical performance and recovery

- Reduced risk of chronic diseases

- Longer lifespan

Think of core sleep as the minimum payment on a credit card—it keeps you out of trouble but doesn't build wealth. Optimal sleep is like making full payments—it builds health and performance capital.

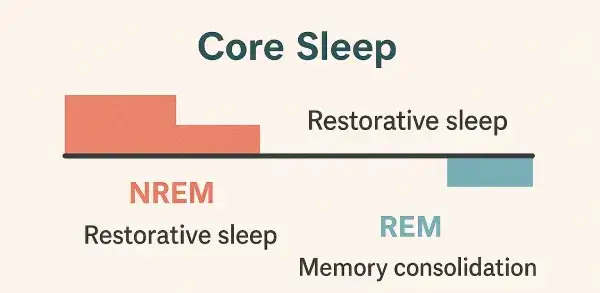

Core Sleep Architecture: What Must Happen

Not all sleep is created equal. Core sleep requires specific sleep architecture to meet your body's essential needs.

Essential Sleep Stages in Core Sleep

For sleep to qualify as core sleep, it must include adequate amounts of these critical stages:

Deep Sleep (N3): The Foundation

Deep sleep is the most critical component of core sleep. During this stage:

- Growth hormone is released, essential for tissue repair

- The glymphatic system clears metabolic waste from the brain

- Immune function is strengthened

- Physical restoration occurs

- Memory consolidation takes place

Without adequate deep sleep, you'll experience physical fatigue, impaired immune function, and difficulty with memory and learning.

REM Sleep: The Cognitive Component

REM sleep is essential for:

- Emotional processing and regulation

- Creative problem-solving

- Procedural memory consolidation

- Brain plasticity and neural reorganization

Insufficient REM sleep can lead to emotional instability, impaired creativity, and difficulty with complex tasks.

Light Sleep (N2): The Processing Stage

Light sleep supports:

- Memory consolidation

- Information processing

- Neural organization

- Preparation for deeper sleep stages

Timing Matters: The First Half of the Night

Core sleep is most effective when it occurs during the first half of your sleep period, when:

- Deep sleep is most abundant

- Sleep is most restorative

- Circadian rhythms are optimally aligned

- Sleep efficiency is highest

This is why "banking" sleep by going to bed early is more effective than trying to "catch up" by sleeping late.

Individual Variation in Core Sleep Needs

While there are general guidelines for core sleep, individual needs vary significantly based on multiple factors.

Genetic Factors

Research has identified specific genes that influence sleep need:

- DEC2 gene: Some people with this gene mutation naturally need only 6 hours of sleep

- ABCC9 gene: Influences sleep duration and quality

- Clock genes: Affect circadian rhythm and sleep timing

These genetic differences explain why some people feel great on 6 hours while others need 9 hours to function optimally.

Age-Related Changes

Core sleep needs change throughout life:

- Infants (0-3 months): 14-17 hours total sleep

- Children (6-13 years): 9-11 hours

- Teenagers (14-17 years): 8-10 hours

- Adults (18-64 years): 7-9 hours (core: 5-6 hours)

- Older adults (65+): 7-8 hours (core: 5-6 hours)

However, older adults often experience changes in sleep architecture, with less deep sleep and more fragmented sleep.

Lifestyle and Health Factors

Several factors can increase your core sleep needs:

- Physical activity: Exercise increases the need for deep sleep

- Mental stress: High stress levels require more REM sleep

- Illness or injury: Recovery requires additional sleep

- Pregnancy: Increased metabolic demands require more sleep

- Medications: Some medications affect sleep quality and need

How to Identify Your Core Sleep Needs

Determining your personal core sleep needs requires careful observation and experimentation. Here's a systematic approach to identify your requirements.

The Sleep Tracking Method

Track your sleep for 1-2 weeks using this approach:

- Start with your current sleep schedule and note how you feel

- Gradually reduce sleep time by 15-30 minutes every few days

- Monitor your symptoms of sleep deprivation

- Identify the breaking point where function significantly declines

- Add 30 minutes back to find your core sleep need

Signs of Insufficient Core Sleep

Watch for these indicators that you're not getting enough core sleep:

- Daytime sleepiness: Falling asleep during quiet activities

- Cognitive impairment: Difficulty concentrating, memory problems

- Emotional changes: Irritability, mood swings, anxiety

- Physical symptoms: Fatigue, muscle weakness, frequent illness

- Performance decline: Reduced productivity, increased errors

The Weekend Test

A simple way to estimate your core sleep need:

- Go to bed when you're naturally tired (no alarm)

- Sleep until you wake up naturally

- Do this for 3-4 consecutive nights

- Average the sleep duration to estimate your need

This method works best when you're not sleep-deprived and don't have external time constraints.

Professional Assessment

For more accurate assessment, consider:

- Sleep diary: Detailed tracking of sleep patterns and symptoms

- Actigraphy: Wearable device that tracks sleep-wake patterns

- Sleep study: Professional assessment in a sleep lab

- Consultation: Discussion with a sleep specialist

Consequences of Insufficient Core Sleep

Failing to meet your core sleep needs has serious consequences for health, performance, and well-being.

Immediate Effects

Within days of insufficient core sleep, you may experience:

- Cognitive impairment: Reduced attention, memory, and decision-making

- Emotional instability: Increased irritability, anxiety, and depression

- Physical symptoms: Fatigue, muscle weakness, coordination problems

- Performance decline: Reduced productivity and increased errors

- Safety risks: Increased risk of accidents and injuries

Long-term Health Consequences

Chronic insufficient core sleep increases risk for:

- Cardiovascular disease: Heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke

- Metabolic disorders: Diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome

- Immune dysfunction: Increased susceptibility to infections

- Mental health issues: Depression, anxiety, mood disorders

- Neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer's disease, dementia

- Cancer: Increased risk of certain cancers

Performance and Productivity Impact

Insufficient core sleep affects:

- Work performance: Reduced productivity, creativity, and problem-solving

- Learning: Impaired memory consolidation and skill acquisition

- Relationships: Increased conflict and reduced empathy

- Safety: Higher risk of accidents in all activities

Research shows that sleep deprivation can impair performance as much as alcohol intoxication, with 24 hours of sleep deprivation equivalent to a blood alcohol concentration of 0.10%.

Optimizing Your Core Sleep

Even when you can't get optimal sleep, you can maximize the quality and effectiveness of your core sleep.

Sleep Quality Optimization

Focus on getting the most restorative sleep possible:

- Prioritize deep sleep: Create conditions that promote deep sleep

- Optimize sleep environment: Cool, dark, quiet, comfortable

- Minimize disruptions: Reduce noise, light, and interruptions

- Use sleep tracking: Monitor sleep stages to ensure adequate deep and REM sleep

Circadian Rhythm Alignment

Align your sleep with your natural rhythms:

- Consistent schedule: Go to bed and wake up at the same time daily

- Light exposure: Get bright light in the morning, reduce evening light

- Temperature regulation: Cool bedroom (65-68°F/18-20°C)

- Timing optimization: Sleep during your natural sleep window

Sleep Hygiene for Core Sleep

Implement practices that support quality sleep:

- Pre-sleep routine: Relaxing activities before bed

- Limit stimulants: Avoid caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol

- Screen management: Reduce blue light exposure in the evening

- Stress management: Techniques to reduce pre-sleep anxiety

- Exercise timing: Avoid vigorous exercise close to bedtime

Strategic Sleep Banking

When you know you'll have limited sleep time:

- Pre-sleep banking: Get extra sleep before anticipated sleep restriction

- Power naps: Short naps (10-20 minutes) to supplement core sleep

- Sleep debt management: Plan recovery sleep after periods of restriction

- Priority sleep: Focus on the most restorative sleep periods

Special Circumstances and Core Sleep

Certain situations require special consideration for maintaining adequate core sleep.

Shift Work and Irregular Schedules

Shift workers face unique challenges in meeting core sleep needs:

- Circadian disruption: Working against natural sleep rhythms

- Sleep fragmentation: Difficulty maintaining continuous sleep

- Reduced sleep quality: Less deep and REM sleep

- Increased sleep need: May require more sleep to compensate

Strategies for shift workers:

- Strategic napping: Short naps before and during shifts

- Light management: Use bright light during work, dark during sleep

- Sleep environment: Create optimal conditions for daytime sleep

- Schedule optimization: Plan sleep periods during natural sleep windows

Travel and Jet Lag

Travel can disrupt core sleep patterns:

- Time zone changes: Circadian rhythm disruption

- Sleep environment changes: Unfamiliar sleeping conditions

- Travel stress: Anxiety and excitement affecting sleep

- Schedule disruption: Irregular meal and activity times

Strategies for travel:

- Gradual adjustment: Shift sleep schedule before travel

- Light exposure: Strategic light exposure to reset circadian rhythm

- Melatonin supplementation: Can help with jet lag

- Sleep environment replication: Bring familiar sleep items

Medical Conditions and Medications

Certain conditions affect core sleep needs:

- Sleep disorders: Sleep apnea, insomnia, restless leg syndrome

- Mental health conditions: Depression, anxiety, PTSD

- Chronic pain: Can interfere with sleep quality

- Medications: Some medications affect sleep architecture

Management strategies:

- Medical treatment: Address underlying conditions

- Sleep specialist consultation: Professional assessment and treatment

- Medication review: Discuss sleep effects with healthcare providers

- Adaptive strategies: Modify sleep practices for specific conditions

Conclusion

Core sleep represents the essential, non-negotiable foundation of your sleep health. Understanding and meeting your core sleep needs is crucial for maintaining basic biological function, preventing serious health consequences, and supporting overall well-being.

While core sleep provides the minimum required for survival, it's important to remember that optimal health and performance require more than the bare minimum. Strive to get both adequate core sleep and additional restorative sleep whenever possible.

By identifying your personal core sleep needs, optimizing your sleep environment and habits, and developing strategies for challenging circumstances, you can ensure that you meet your essential sleep requirements even in our busy, demanding world.

Remember that sleep is not a luxury—it's a biological necessity. Prioritizing your core sleep needs is one of the most important investments you can make in your health, performance, and quality of life.

References

- Walker, M. P. (2017). Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Scribner.

- Hirshkowitz, M., et al. (2015). National Sleep Foundation's sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40-43.

- Watson, N. F., et al. (2015). Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep, 38(6), 843-844.

- Basner, M., et al. (2013). Sleep duration in the United States 2003-2016: first signs of success in the fight against sleep deficiency? Sleep, 41(2), zsy012.

- Killgore, W. D. (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Progress in Brain Research, 185, 105-129.

- Dinges, D. F., et al. (1997). Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep, 20(4), 267-277.

- Van Dongen, H. P., et al. (2003). The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep, 26(2), 117-126.

- Buysse, D. J. (2014). Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep, 37(1), 9-17.